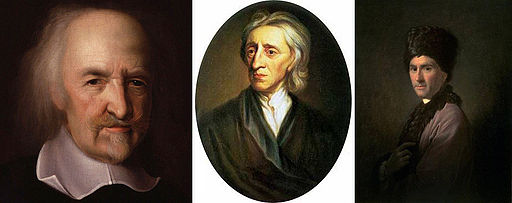

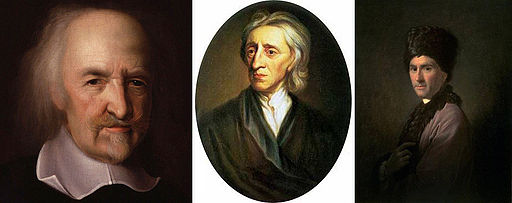

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and John Locke (1632–1704) in England, and Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) in France (pictured above left to right), were among the philosophers who developed a theory of natural rights based on rights to life, liberty, and property (later expanded by Jefferson to “the pursuit of happiness”) that individuals would have in a prepolitical “state of nature.” (Image, public domain)

The concept of natural rights occupies an important place in American political thought as reflected in the Declaration of Independence. In the Declaration, primarily authored by Thomas Jefferson, the Second Continental Congress asserted the “self-evident” truths that “all men are created equal” and entitled to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The Declaration then proceeds to excoriate King George III and Parliament for denying such human rights. Jefferson justifies colonial revolution because of this denial of rights.

Many scholars think that the idea of natural rights emerged from natural law, a theory evident in the philosophy of the medieval Catholic philosopher St. Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274). Natural law was thought to embody principles of right and wrong — especially pertaining to relations between and among individuals — that could be ascertained by human reason, apart from divine revelation. Philosophers, however, were rarely in complete agreement as to the content of such laws. For example, they disagreed over whether natural law prohibits human slavery, as American abolitionists later argued.

As philosophers applied the concept of natural rights to the secular world, the focus shifted from rules concerning individual behavior to claims of rights that individuals could make against the state. Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and John Locke (1632–1704) in England, and Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) in France, were among the philosophers who developed a theory of natural rights based on rights to life, liberty, and property (later expanded by Jefferson to “the pursuit of happiness”) that individuals would have in a prepolitical “state of nature.” Some of these rights, especially those pertaining to the relation of individuals to their Creator, were paramount, and in the words of the Declaration of Independence,“unalienable.”

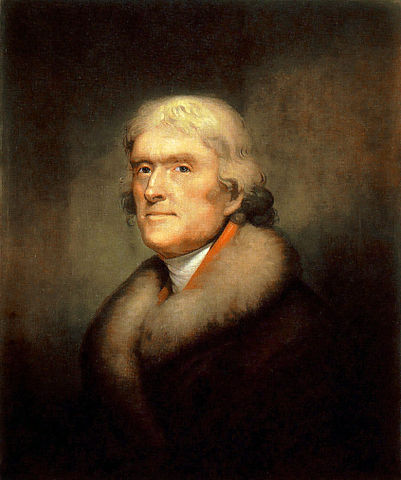

The concept of natural rights occupies an important place in American political thought as reflected in the Declaration of Independence. In the Declaration, primarily authored by Thomas Jefferson (pictured above), the Second Continental Congress asserted the “self-evident” truths that “all men are created equal” and entitled to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The Declaration then proceeds to excoriate King George III and Parliament for denying such human rights. Jefferson justifies colonial revolution because of this denial of rights. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Although the First Amendment was originally third on the list of original proposals in the Bill of Rights that Congress submitted to the states for approval, it was the first amendment to deal with individual rights. Almost without exception, the rights in the First Amendment are thought to be fundamental because they deal with matters of conscience, thought, and expression.

The two religion clauses are designed to allow individuals to follow their conscience in matters of faith and worship, which some believe could determine eternal destinies, a basis for the argument that James Madison made in his “Memorial and Remonstrance” and in the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.

Clauses relative to speech, press, peaceable assembly, and petition are designed to promote discussion and debate concerning the kind of governmental policies that suit a republican, or representative, form of government, and arguably to promote the development of the individual’s personality. Perhaps as a result, courts were slow to recognize rights surrounding commercial speech.

It is doubtful that George Mason and the authors of the provisions in the First Amendment would have claimed to have originated the rights inherent in the amendment; it is more likely that they would have traced their origins to contemporary documents, including state bills or declarations of rights. Indeed, the Federalists’ initial opposition to the Bill of Rights stemmed in part from the belief that such rights were inherent liberties that did not need to be stated. By contrast, there are some provisions — such as the Fifth Amendment’s prohibition against double jeopardy or the Sixth Amendment’s requirement of trial by jury — that are clearly man-made mechanisms for enforcing fundamental principles of fairness, not morally mandated rights per se.

Rights embodied within documents are constitutional, or civil, rights, which serve to shape the values shared by a people. In the U.S. system, individuals can bring claims of such rights to courts, which have the power to enforce them. With the possible exception of equality, which was later recognized in the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (1868), it is difficult to identify any rights outside the First Amendment that are more closely associated with the concept of natural rights; from this stem the arguments that these rights should enjoy a “preferred position” and that they are relatively absolute.

Embodying such rights within a written text is designed to preclude the necessity for resorting to extralegal means for securing their protection, but such rights would arguably be legitimate moral claims even if they were not embodied in the constitutional text. For example, the Supreme Court has on occasion made decisions on the basis of unenumerated general moral principles, or natural rights, rather than on the basis of a specific constitutional provision. Some believe the modern right to privacy is such a judicially created right.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.